Accordingly, the High Court cases on jurisdictional error are also cases on error of law. The common law rules relating to judicial review of administrative decisions are well established. They apply where administrative action is not authorised or where the decision-maker misunderstands the authorisation or exceeds it.

They require a fair hearing, both through an unbiased decision-maker and a fair process. They require the decision-maker to act on all materially significant matters and not to ignore significant matters. The action must involve a real exercise of discretion and the power must be exercised bona fide. Other, more detailed, descriptions of the requirements of the common law tend to be particulars of the more general powers. The other type of 'judicial review' does not involve the actions of the executive branch, but rather the actions of the legislative branch.

52 of theConstitution Act, 1982provides that "the Constitution of Canada is the supreme law of Canada". 24 of the same Act guarantees the right for individuals to challenge legislation which does not conform with the Constitution thereby giving Canadian courts the power to engage in 'judicial review' on the constitutionality of legislation. The purpose of this type of 'judicial review', also referred to as "constitutional review", is to ensure that legislation conforms to the Constitution of Canada. The Constitution regulates two different areas – the division of powers between the federal and provincial government, and the rights guaranteed to every Canadian against both levels of government.

Judicial Review Meaning In Law Consequently, there are two ways in which an act of a legislature or of Parliament might be unconstitutional. First, when the act is enacted by a provincial government while the relevant subject matter of the act is under Federal jurisdiction . As a particular example, we examine controversies surrounding the scope of review under the ALL in sections entitled "A comparative perspective on the scope of review" and "Innovations in the 2018 SPC interpretation" below. Conventional wisdom has it that the scope of judicial review in China is too narrow.

We show that from a comparative administrative law perspective, the scope of review under pre-2015 practice was in fact quite normal. Rather, it is the effort to extend such scope since 2015 that is unusual by international standards. Registering this issue indeed allows us to identify an important rolling back of judicial authority implied by recent reforms. The rise of CCs began after WW II and gained momentum in recent processes of constitutional transition. The rules for the selection of judges seek to reconcile democratic legitimacy and safeguards for independence. CCs' jurisdiction typically includes judicial review of legislation and adjudication of constitutional disputes.

Despite the politicized appointment process institutional interest forces, CCs to prove their independence. To a certain extent they have given up the ideal-typical judicial style of decision making for a political one (e.g., by being active rather than reactive, broad construction of open-textured constitutional texts and flexible forms of judicial decision-making). Interestingly, this approach bears resemblances to the US federal doctrine on judicial review. US courts' standard of review of agency statutory interpretation also depends on the ways in which an agency's position is developed.

When formal regulations (i.e., mostly rules that have gone through the notice and comment procedure required by the APA) are at stake, courts apply the "Chevron test," which in many instances leads to a high level of deference . By contrast, if only an informal policy position serves as the ground of agency action, courts apply the less deferential "Skidmore standard" . While under both types of standards, courts have been observed to be more likely to defer to agency actions than not, the varying standards of review clearly give courts greater interpretive authority in some circumstances than in others. How to characterise these standards thus has been an obsession of US legal scholars (Vermeule 2017; Stack 2018).

The prevalence of these constraints on the "scope of judicial review" in liberal democracies has two implications. First, these constraints do not in themselves render the ALL either exceptional or inadequate. Second, modifying these constraints could involve relatively unusual institutional design, given the parameters of a civil law judiciary .

The 2015 ALL and 2018 SPC Interpretation precisely advance such unusual design. In many liberal democracies, the standard of judicial review has attracted extensive attention from administrative law practitioners and scholars. By contrast, although the issue has also inevitably arisen in Chinese practice, it has received very limited attention from commentators. Importantly, it is along this neglected dimension that the 2015 ALL and the 2018 SPC Interpretation have dealt a setback to judicial review.

The judicial review of government actions is often used as a bellwether of the government's attitude towards the rule of law in China. Accordingly, in gauging the direction of legal reform in the Xi era, media reports have highlighted changes in litigation against government agencies as evidence of positive movement towards greater rule of law. We provide a selective review of changes in China's administrative litigation system in the last few years, giving special attention to the amendment in 2014 of the Administrative Litigation Law , and a 2018 Supreme People's Court Interpretation of the same statute.

In our view, the question of whether lawsuits might be brought against the government has arguably been superseded in importance by the question of how courts will decide such lawsuits. And the generic notion of judicial independence itself no longer sheds sufficient light on actual and possible judicial responses. These aspects of German administrative law illustrate the alien nature of pre-enforcement review to civil law courts. However, it is important to emphasise that limitations on pre-enforcement review arise not only in civil law countries. In the United States, pre-enforcement review of federal agency actions is strongly tied to the "notice and comment" procedural requirement for rule-making under the Administrative Procedure Act .

But for the APA, traditional justiciability doctrines would impose substantial restrictions on pre-enforcement review . It is now recognised among comparative administrative law scholars that the APA itself is a very American institution, and notice and comment procedures are relatively rare in parliamentary political systems (Jensen and McGrath 2011; Stiglitz and Figueiredo 2017). In other words, as far as we can tell, the practice of pre-enforcement review of agency regulations is sustained critically by procedural requirements on rulemaking, and these procedural requirements are themselves rare creatures. Consequently, even in common law jurisdictions such as Canada, the UK, and Australia, pre-enforcement reviews are rare. Second, Chinese scholars and policymakers have yet to articulate a normative framework for conceptualising what forms enhanced judicial power should take. Should it, for example, be courts' frequent use of various sanctions of agency misconduct in the course of litigation, of the power to make judicial recommendations for amending or repealing illegal IPDs, or of the authority to retry cases?

Or should it, again for example, be the ability of individual judges to introduce policy considerations into adjudication through reviewing the reasonableness of IPDs ? Arguably, this theme has largely been absent from Chinese discourse in reforming the ALL. Under the 2015 ALL, individuals, organisations, or legal persons may file a lawsuit if they believe that an "administrative action" violates their legal rights and interests . The term "administrative action" replaced the term "concrete administrative action" in the 1989 ALL, although this drafting change has little significance in itself in expanding the scope of review. This is basically because the 2015 ALL retains a provision from the 1989 ALL that excludes four categories of government actions from judicial review – including formal and informal rulemaking. More substantively, Article 2 extends the definition of "administrative action" to include decisions made by organisations authorised to exercise administrative mandates, such as universities and some regulatory bodies.

While all government actions encroaching on the personal and property rights of plaintiffs can be challenged , the new statutory enumeration seemed to identify areas where the need to cope with social resentment and unrest is most urgent. Most modern legal systems allow the courts to review administrative "acts" . In most systems, this also includes review of secondary legislation . Some countries have implemented a system of administrative courts which are charged with resolving disputes between members of the public and the administration, regardless these courts are part of administration or judiciary .

In other countries , judicial review is carried out by regular civil courts although it may be delegated to specialized panels within these courts . It is quite common that before a request for judicial review of an administrative act is filed with a court, certain preliminary conditions must be fulfilled. In most countries, the courts apply special procedures in administrative cases. The logic of the two restrictions on the scope of judicial review is best explained in reverse order.

First, there is an obvious explanation why Chinese courts may not be permitted to "strike down" problematic agency rules. This has to do with the idea that civil law judiciaries, on which the Chinese judiciary is modelled, are generally expected to apply the law, not to make law. Relatedly, decisions by civil law courts generally do not have precedential value, because they do not create norms of general application. While some modern courts in civil law countries present exceptions to these general rules, the rules continue to characterise the power of most civil law courts.

Precluding formal regulations from reinforcement clearly raises suspicions of both law-making (i.e., revoking binding law) and claiming to set precedents, while precluding IPDs from enforcement also sets precedents. This basic logic is supported by the fact that, in civil law countries, the ability of courts to invalidate agency rules seems to be the exception, not the rule. Is the institutional capacity of courts of law to determine the constitutional validity of actions taken by either coordinate or inferior branches of government. Enabling government while at the same time protecting against the potential abuse of governmental power is an age-old, and continuing, dilemma of a constitutional democracies. In modern democracies, however, judicial review presents its own dilemma—how to rationalize limits on majority rule. The term judicial review refers to a court's review of a decision of a lower court in order to determine whether an error was made.

When speaking of the Supreme Court, the term also refers to the Court's power to pass judgment on the constitutionality of actions of state and federal legislatures and courts. The most common form of judicial review is the review of a lower court decision by a higher court, whether it be state or federal. Courts usually review these decisions in the appeals process, when a losing party in a case claims an error was made and appeals to the higher court to examine the decision.

Specifically, in the case of an IPD found to be illegal, a court, after entering a decision on the particular dispute, shall issue "disposition recommendations" to the agency promulgating the IPD. It may also copy "the People's government at the same level as the agency, any agency at the next higher level, the supervisory authority, and any recordation authority of the IPD" on the recommendation. The continued existence of rights to judicial review at common law, alongside statutory rights of review, has inevitably tended to lead to decisions which equate the two. Moreover, the convenience of the statement of grounds in the AD Act has tended to influence the common law grounds. It is not impossible, however, that the rigid statutory statement of the grounds, coupled with their being read as restating the common law, has lead to some limitation in the development of grounds of review both at common law, and under s 5.

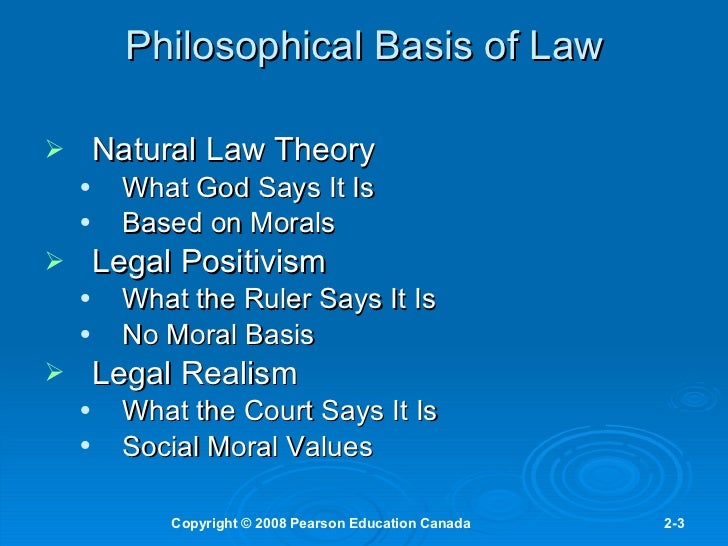

In fact, the idea that the courts have the power to strike down laws duly passed by the legislature is not much older than is the United States. In the civil law system, judges are seen as those who apply the law, with no power to create legal principles. In the common law system, on which American law is based, judges are seen as sources of law, capable of creating new legal principles, and also capable of rejecting legal principles that are no longer valid. However, as Britain has no Constitution, the principle that a court could strike down a law as being unconstitutional was not relevant in Britain. Moreover, even to this day, Britain has an attachment to the idea of legislative supremacy.

Therefore, judges in the United Kingdom do not have the power to strike down legislation. The first type of 'judicial review' involves the actions of the executive branch of government. In the modern state it is impossible for the legislature to address every administrative decision , therefore, many statutes endow various governmental authorities with administrative powers. If the court finds in favour of the plaintiff, it can annul the administrative decision.

When exercising the power of judicial review the court is expected to act with judicial restraint. This means that they can only decide on the constitutionality of an issue. In most cases, the court respects the precedent, or past decisions, of lower courts. Justices on the court cannot use a case to inject their own political feelings on a particular issue.

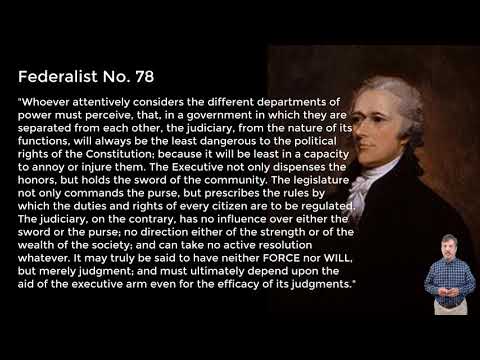

Judicial review gives them the power to only decide if a particular law or action by a government official was legal based upon the Constitution. The Supreme Court plays a very important role in our constitutional system of government. First, as the highest court in the land, it is the court of last resort for those looking for justice. Second, due to its power of judicial review, it plays an essential role in ensuring that each branch of government recognizes the limits of its own power.

Third, it protects civil rights and liberties by striking down laws that violate the Constitution. Finally, it sets appropriate limits on democratic government by ensuring that popular majorities cannot pass laws that harm and/or take undue advantage of unpopular minorities. In essence, it serves to ensure that the changing views of a majority do not undermine the fundamental values common to all Americans, i.e., freedom of speech, freedom of religion, and due process of law.

If a court cannot strike down formal or informal agency rules, it should also not hear disputes the main purpose of which is to challenge the validity of such rules – the reviewing court would not be able to provide any remedy. It has long been conventional wisdom among commentators on Chinese administrative law that these parameters for judicial review were too restrictive (He 2018; Tong 2015). Although the limitations upon the issue of the constitutional writs continue to apply, two important factors have nevertheless permitted the reach of common law judicial review to expand.

The first is the expansion of what amounts to jurisdictional error. It has now been relegated, at least, to secondary status in the United Kingdom because of this. The High Court has specifically avoided spelling out the content of jurisdictional error, although recognising the difficulty of distinguishing jurisdictional error from non-jurisdictional error. Broadly, jurisdictional error arises "if the decision-maker makes a decision outside the limits of the function and powers conferred on him or her, or does something which he or she lacks power to do".

It is for the Commission to set out its reasoning in a clear and unequivocal fashion, to enable the persons concerned to ascertain the grounds for the measure and the competent court to exercise its power of review. As concerns the appeal before the Court of Justice, it is limited to points of law . Assessment of the facts does not constitute a question of law submitted as such for review by the Court of Justice save where there has been a distortion of the facts or evidence. In the context of competition, the approach initially followed by the Court of Justice was very careful as regards the scope and the intensity of its own review of the Commission's decisions, as shown in the leading case Consten and Grundig.

This jurisprudential line has been progressively replaced by a more intense scrutiny in competition cases . The first one was the jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights concerning Article 6 of the Convention, that provides the guarantee of fair trial, which encompasses the provision of "full jurisdiction", in presence of an infringement of criminal nature. In the seminal ruling Engel, the Court of Human Rights stated that the criminal nature of the infringement is affirmed if the sanction is severe and has deterrence as function.

This is the case of the sanction provided by competition law, as affirmed in another landmark decision, in the Menarini case. As a consequence, the judicial review of competition decisions should be extended to all the questions of facts and laws concerning the administrative decision. The second factor was the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union which, after the Treaty of Lisbon , has the same legal value of the Treaties.

Competition decisions should comply with the Charter and, in particular, with the presumption of innocence, the right to fair proceedings and the right to effective judicial remedy. As a consequence of all these factors, the judicial review in competition matters has become high-intensive. Judicial review is a particularly important aspect of the constitutional settlement in the UK. It is a process, a court case, where a judge or judges decide whether a public body has behaved lawfully.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.